Dependency Engine for Deep Learning

运行的更快, 可以扩展到更大的数据集上是深度学习库永远的主题. 为了做到这一点一个自然的决定是不能仅仅使用一个设备 (GPU), 而且要充分利用更多的计算资源.

当库的设计者开始思考这个问题的时候,

When library designer started to think about this problem, one natural theme will occur.

How can we parallelize the computation across devices? More importantly,

how do we synchronize the computation when we introduce multi-threading?

Runtime dependency engine is a generic solution to such problems. This article discusses

the runtime dependency scheduling problem in deep learning. We will introduce the dependency

scheduling problem, how it can help make multi-device deep learning easier and faster, and

discuss possible designs of a generic dependency engine that is library and operation independent.

Most design details of this article inspires the dependency engine of mxnet, with the dependency tracking algorithm majorly contributed by Yutian Li and Mingjie Wang.

Dependency Scheduling Problem

While most of the users want to take advantage of parallel computation,

most of us are more used to serial programs. So it is interesting to ask

if we can write serial programs, and build a library to automatically parallelize

operations for you in an asynchronized way.

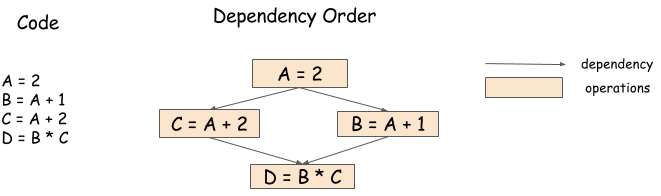

For example, in the following code snippet. We can actually run B = A + 1

and C = A + 2 in any order, or in parallel.

A = 2

B = A + 1

C = A + 2

D = B * C

However, it is quite hard to code the sequence manually, as the last operation,

D = B * C, needs to wait for both the above operations to complete before it starts running.

We can represent the computation as the following dependency graph.

Dep Simple

Dep Simple

In this specific case, the graph is also called data-flow graph, as it represents the dependency

in terms of data and computation.

A dependency engine is a library that takes some sequence of operations, and schedules them

correctly according to the dependency pattern, and potentially in parallel. So in the toy example,

a dependency library could run B = A + 1 and C = A + 2 in parallel, and run D = B * C

after both operations complete.

Problems in Dependency Scheduling

In last section we introduced what is dependency engine mean in this article. It seems a quite interesting

thing to use as it relieves our burden from writing concurrent programs. However, as things go parallel,

there are new (dependency tracking)problems that arises which need to be solved in order to make the running

program correct and efficient. In this section, let us discuss the problems we will encounter in deep

learning libraries when things go parallel.

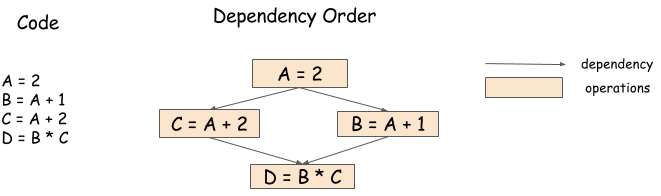

Data Flow Dependency

The central thing that almost every dependency engine will have to solve, is the dataflow dependency problem.

Dep Simple

Dep Simple

Data Flow dependency describes how the outcome of one computation can be used in other computations.

As we have elaborated this in last section, we will only put the same figure here. Libraries that have

data flow tracking engines include Minerva and Purine2.

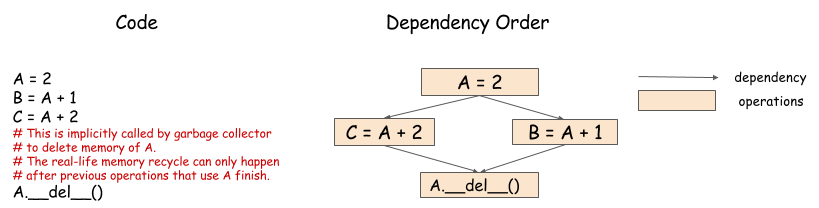

Correct Memory Recycle

One problem that we will encounter is when to recycle memory we allocated to the arrays.

This is simple in the serial case. Because we can simply recycle the memory after the variable

go out of scope. However, things becomes a bit harder in parallel case. Consider the following

example

Dep Del

Dep Del

In the above example, because both computation needs to use values from A. We cannot perform

the memory recycling before these computation completes. So a correct engine

need to schedule the memory recycle operations according to the dependency, and make sure it

is executed after both B = A + 1 and C = A + 2 completes.

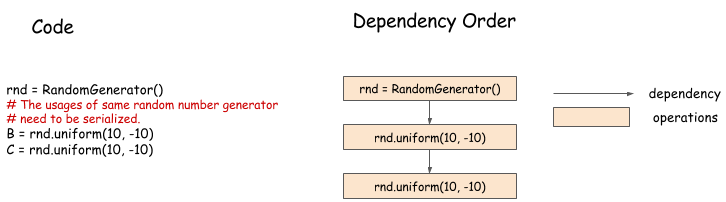

Random Number Generation

Random number generators are commonly used in machine learning. However, they also bring

interesting challenges for dependency engine. Consider the following example

Dep Rand

Dep Rand

Here we are generating random numbers in a sequence. While it seems that the two random number

generations can be parallelized. This is usually not the case. Because usually a pseudorandom

number generator (PRNG) is not thread-safe because it might contain some internal state to mutate

when generating a new number. Even if the PRNG is thread-safe, it is still desirable to

run the generation in the a serialized way, so we can get reproducible random numbers.

So in this case, actually what we might want to do is to serialize the operations that uses the same PRNG.

Case Study on Multi-GPU Neural Net

In the last section, we have discussed the problem we may facing in dependency engine.

But before thinking about how we can design a generic engine to solve this problems.

Let us first talk about how can dependency engine help in multi GPU training of neural net.

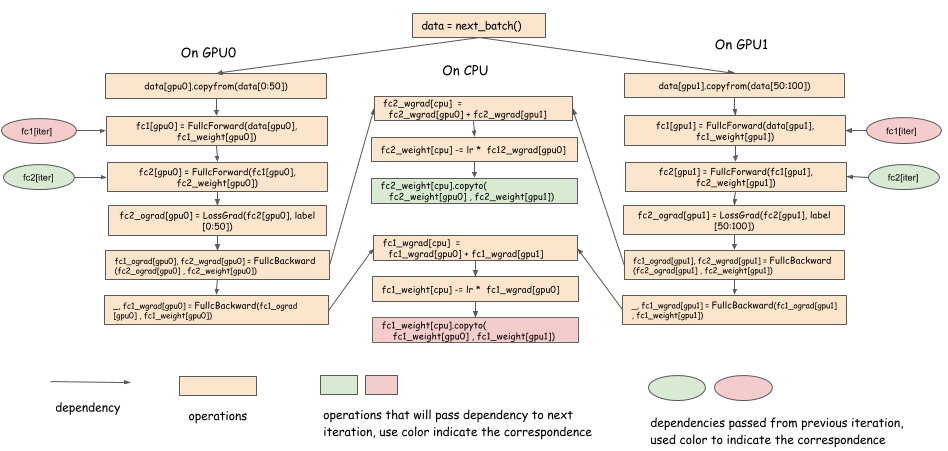

The following is a pseudo python program that describes one batch training of two layer

neural net.

# Example of one iteration Two GPU neural Net

data = next_batch()

data[gpu0].copyfrom(data[0:50])

data[gpu1].copyfrom(data[50:100])

# forward, backprop on GPU 0

fc1[gpu0] = FullcForward(data[gpu0], fc1_weight[gpu0])

fc2[gpu0] = FullcForward(fc1[gpu0], fc2_weight[gpu0])

fc2_ograd[gpu0] = LossGrad(fc2[gpu0], label[0:50])

fc1_ograd[gpu0], fc2_wgrad[gpu0] =

FullcBackward(fc2_ograd[gpu0] , fc2_weight[gpu0])

_, fc1_wgrad[gpu0] = FullcBackward(fc1_ograd[gpu0] , fc1_weight[gpu0])

# forward, backprop on GPU 1

fc1[gpu1] = FullcForward(data[gpu1], fc1_weight[gpu1])

fc2[gpu1] = FullcForward(fc1[gpu1], fc2_weight[gpu1])

fc2_ograd[gpu1] = LossGrad(fc2[gpu1], label[50:100])

fc1_ograd[gpu1], fc2_wgrad[gpu1] =

FullcBackward(fc2_ograd[gpu1] , fc2_weight[gpu1])

_, fc1_wgrad[gpu1] = FullcBackward(fc1_ograd[gpu1] , fc1_weight[gpu1])

# aggregate gradient and update

fc1_wgrad[cpu] = fc1_wgrad[gpu0] + fc1_wgrad[gpu1]

fc2_wgrad[cpu] = fc2_wgrad[gpu0] + fc2_wgrad[gpu1]

fc1_weight[cpu] -= lr * fc1_wgrad[gpu0]

fc2_weight[cpu] -= lr * fc2_wgrad[gpu0]

fc1_weight[cpu].copyto(fc1_weight[gpu0] , fc1_weight[gpu1])

fc2_weight[cpu].copyto(fc2_weight[gpu0] , fc2_weight[gpu1])

In this program, the example 0 to 50 are copied to GPU0 and example 50 to 100

are copied to GPU1. The calculated gradient are aggregated in CPU, which then performs

a simple SGD update, and copies the updated weight back to each GPU.

This is a common data parallel program written in a serial manner.

The following dependency graph shows how it can be parallelized:

Dep Net

Dep Net

Few important notes:

- The copy of gradient to CPU, can happen as soon as we get gradient of that layer.

- The copy back of weight, can also be done as soon as the weight get updated.

- In the forward pass, actually we have a dependency to

fc1_weight[cpu].copyto(fc1_weight[gpu0] , fc1_weight[gpu1])

from previous iteration. - There is a lag of computation between last backward to layer k to next forward call to layer k.

- We can do the weight synchronization of layer k in parallel with other computation in this lag.

The points mentioned in above list is the exact optimization used by multi GPU deep learning libaries such as cxxnet.

The idea is to overlap the weight synchronization(communication) with the computation.

However, as you may find out it is really not easy to do that, as the copy need to be triggered as soon as backward of

that layer completes, which then triggers the reduction, updates etc.

Having a dependency engine to schedule these operations makes our life much easier, by pushing the task of multi-threading

and dependency tracking to the engine.

Design a Generic Dependency Engine

Now hopefully you are convinced that a dependency engine is useful for scaling deep learning programs to multiple devices.

Let us now discuss how we can actually design a generic interface for dependency engine, and how we can implement one.

We need to emphasize that solution discussed in this section is not the only possible design for dependency engine,

but rather an example that we think is useful to most cases.

One of the most goal thing we like to focus on is generic and lightweight. Ideally, we would like the engine

to be easily pluggable to existing deep learning codes, to scale them up to multiple machines with minor modifications.

In order to do so, we need to make less assumption of what user can or cannot do, and focus only on the dependency tracking part.

Here are some summarized goals of engine:

- It should not be aware of operation being performed, so user can do any operations they defined.

- It should not be specific to certain types of object it schedules.

- We may want to schedule dependency on GPU/CPU memory

- We may also want to track dependency on random number generator etc.

- It should not allocate resources, but only tracks the dependency

- The user can allocate their own memory, PRNG etc.

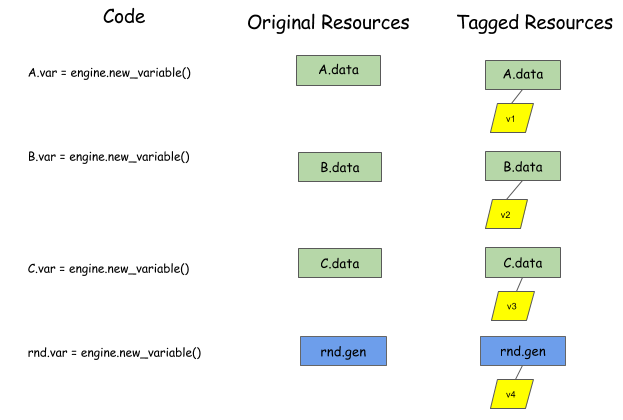

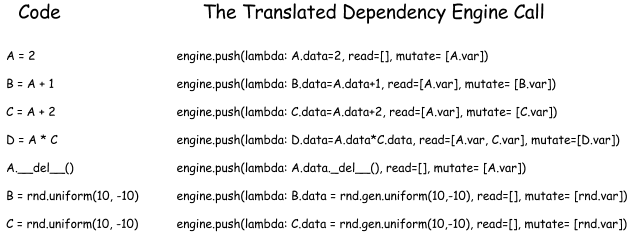

The following python snippet provides a possible engine interface to reach our goal. Note that usually

the real implementation is in C++.

class DepEngine(object):

def new_variable():

"""Return a new variable tag

Returns

-------

vtag : Variable Tag

The token of engine to represent dependencies.

"""

pass

def push(exec_func, read_vars, mutate_vars):

"""Push the operation to the engine.

Parameters

----------

exec_func : callable

The real operation to be performed.

read_vars : list of Variable Tags

The list of variables this operation will read from.

mutate_vars : list of Variable Tags

The list of variables this operation will mutate.

"""

pass

Because we cannot assume the object we are scheduling on. What we can do instead is to ask user to allocate a

virtual tag that is associated with each object to represent what we need to schedule.

So at the beginning, user can allocate the variable tag, and attach it to each of object that we want to schedule.

Dep Net

Dep Net

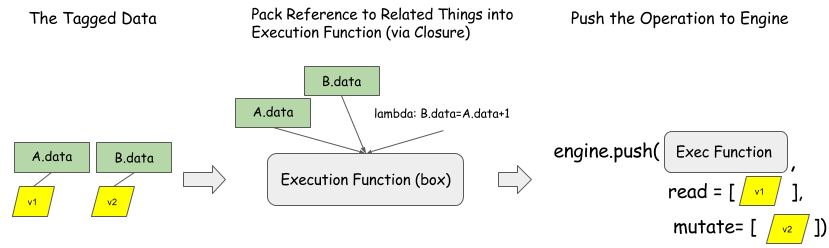

After having the variable tags, user call push to tell the engine about the function we want to execute.

In addition, user need to specify the dependencies of the operation by read_vars and write_vars.

-

read_varsare variable tags of objects which the operation will "read from", without changing its internal state. -

mutate_varsare variable tags of objects which the operation will mutate their internal states.

Push Op

Push Op

The above figure shows how we can push operation B = A + 1 to dependency engine. Here B.data,

A.data are the real allocated space. We should note that engine is only aware of variable tags.

Any the execution function can be any function closures user like to execute. So this interface is generic

to what operation and resources we want to schedule.

As a light touch on how the engine internals works with the tags, we could consider the following code snippet.

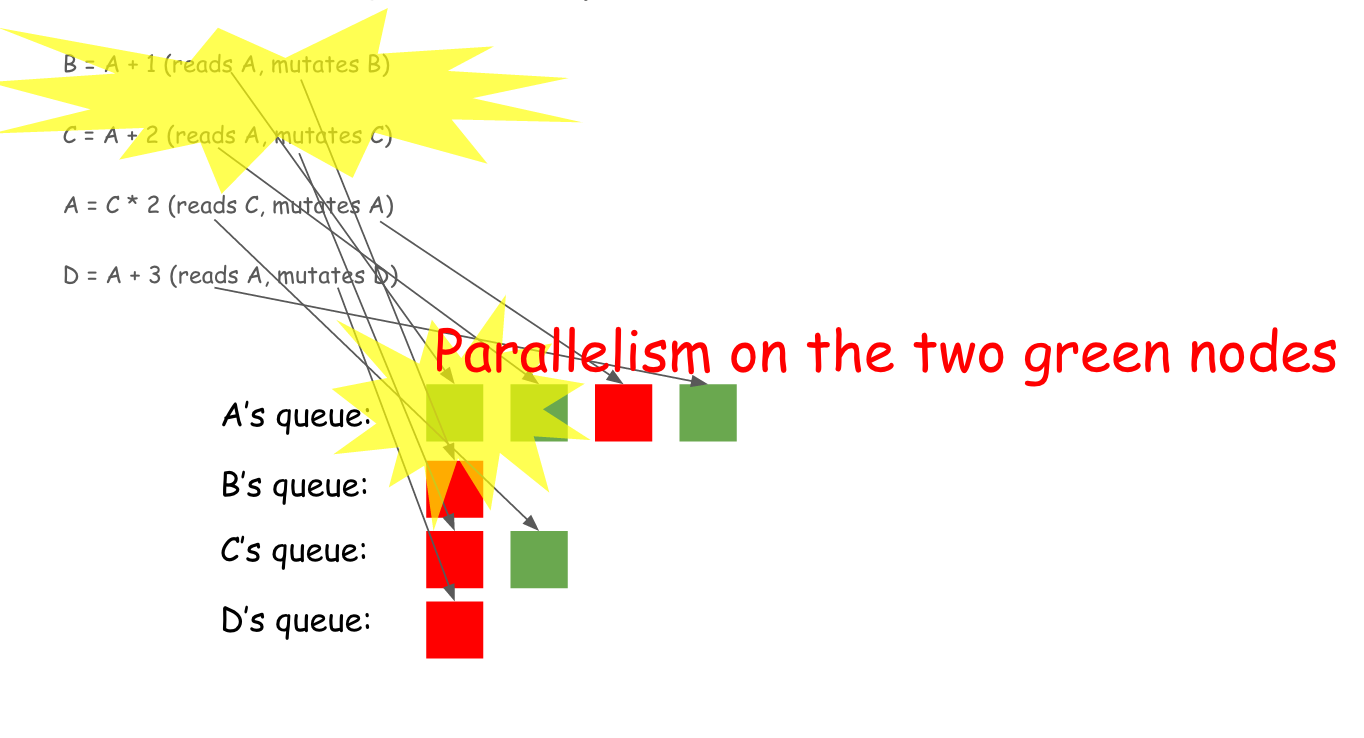

B = A + 1

C = A + 2

A = C * 2

D = A + 3

The first line reads variable A and mutates variable B. The second line reads variable A and mutates variable C. And so on.

The engine is going to maintain a queue for each variable, as the following animation shows for each of the four lines. Green blocks represents a read action, while a red one represents a mutation.

Dependency Queue

Dependency Queue

Upon building this queue, the engine sees that the first two green blocks at the front of A's queue, could actually be run in parallel, because they are both read actions and won't conflict with each other. The following graph illustrates this point.

Dependency Parallelism

Dependency Parallelism

The cool thing about all this scheduling is, it is not confined to numerical calculations. Since everything scheduled is only a tag, the engine could schedule everything!

The following figure gives a complete push sequence of the programs we mentioned in previous sections.

Push Seq

Push Seq

Port Existing Codes to the Dependency Engine

Because the generic interface do not take control of things like memory allocation and what operation to execute.

Most existing code can be scheduled by dependency engine in two steps:

- Allocate the variable tags associates them resources like memory blob, PRNGS.

- Call

pushwith the execution function to be original code to execute, and put the variable tags of

corresponding resources correctly inread_varsandmutate_vars.

Implement the Generic Engine

We have described the generic engine interface and how it can be used to schedule various operations.

How can we implement such an engine. In this section, we provide high level discussion on how such engine

can be implemented.

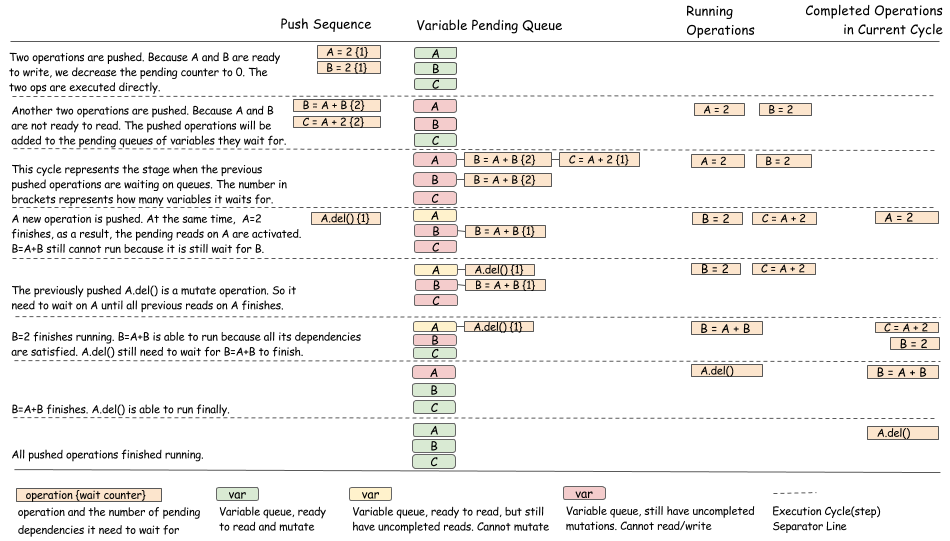

The general idea is as follows

- Use a queue to track all the pending dependencies on each variable tag.

- Use counter on each operation to track how many dependencies are yet to be full-filled.

- When operations are completed, we update the state of the queue and dependency counters to schedule new operations.

The following figure gives a visual example of the scheduling algorithm, which might give you a better sense

of what is going on in the engine.

Dep Tracking

Dep Tracking

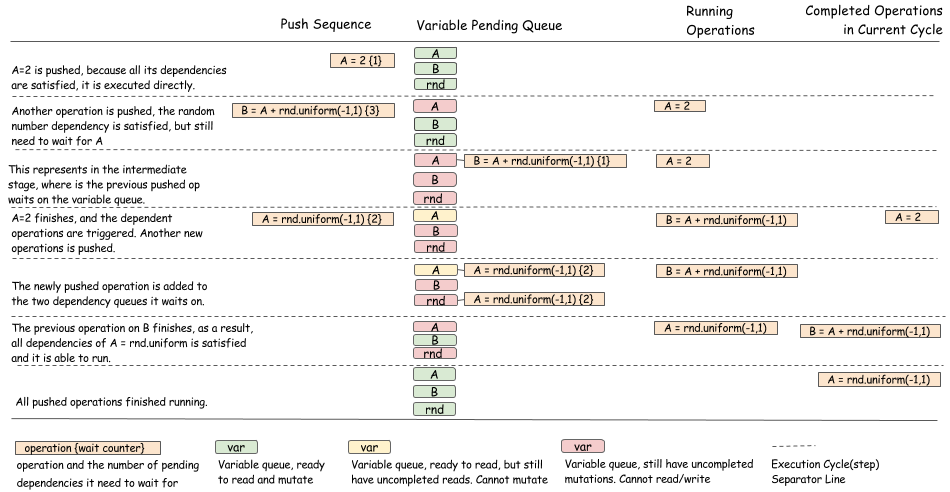

The following figure gives another example that involves random number generations.

Dep Rand

Dep Rand

As we can see, the algorithm is mainly about update pending queues of operations and doing the right

state transition when operation completed. More care should be taken to make sure the state transition

are done in a thread safe way.

Separate Dependency Tracking with Running Policy

If you read carefully, you can find that previous section only shows the algorithm to decide when an operation

can be executed. We did not show how an operation can be run. In practice, there can be many different policies.

For example, we can either use a global thread-pool to run all operations, or use specific thread to run operations

on each device.

This running policy is usually independent of dependency tracking, and can be separated out either as an independent module

or virtual interface of base dependency tracking modules. Having a runtime policy that is fare to all operations and schedule

smoothly is an interesting systems problem itself.

Discussions

We should emphasize that the designs mentioned in this article is not the only solution to the dependency tracking problem,

but is an example on how things can be done. There are several design choices that are debatable.

We will discuss some of of them here.

Dynamic vs Static

The dependency engine interface discussed in this article is somewhat dynamic.

In a sense that user can push operations one by one, instead of declaring the entire dependency graph (static).

The dynamic scheduling may mean more overhead than static declarations, in terms of data structure.

However, it also enables more flexible patterns such as supporting auto parallelism for imperative programs

or mixture of imperative and symbolic programs. Some level of pre-declared operations can also be added

to the interface to enable data structure re-use.

Mutation vs Immutable

The generic engine interface in this article support explicit scheduling for mutation.

In normal dataflow engine, the data are usually immutable. Immutable data have a lot of good properties,

for example, they are usually good for better parallelization, and easier fault tolerance in distributed setting via re-computation.

However, making things purely immutable makes several things hard:

- It is harder to schedule the resource contention problems such as random number and deletion.

- The engine usually need to manage resources (memory, random number) to avoid conflictions.

- It is harder to plug in user allocated space etc.

- No pre-allocated static memory, again because the usual pattern is write to a pre-allocated layer space,

which is not supported is data is immutable.

The mutation semantics makes these issues easier. It is in lower level than a data flow engine, in a sense that if we

allocate a new variable and memory for each operations, it can be used to schedule immutable operations.

But it also makes things like random number generation easier as the operation is indeed mutation of state.

Contribution to this Note

This note is part of our effort to open-source system design notes

for deep learning libraries. You are more welcomed to contribute to this Note, by submitting a pull request.

Source Code of the Generic Dependency Engine

MXNet provides an implementation of generic dependency engine described in this article.

You can find more descriptions in the here. You are also welcome to contribute to the code.

网友评论